Trusty and Wellbeloved Reader,

I’m a bit late continuing this series, but since I’ve been ill for the last few days I’ve had a few minutes to consider the next addition to this little tale of books: my Disputationes.

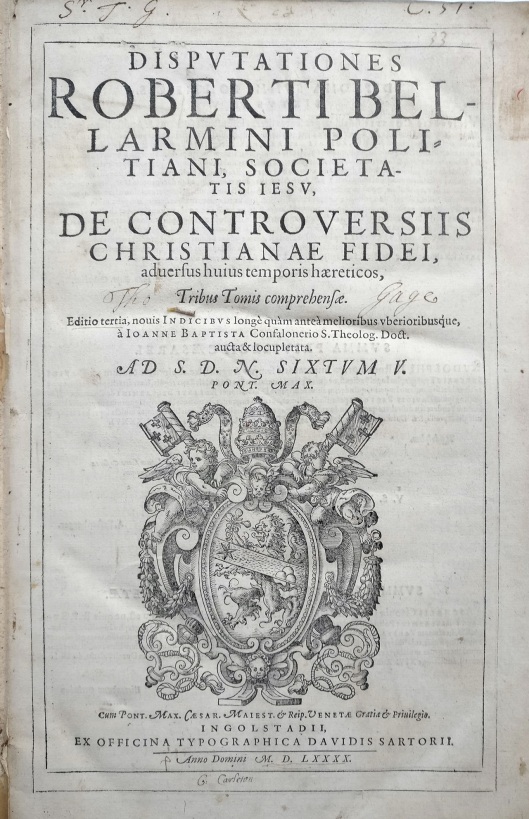

The Disputationes de Controversiis Christianae Fidei adversus hujus temporis Haereticos is a comprehensive defense of Roman Catholic power written at the height of the Protestant reformations across Europe. In them their author, Roberto Bellarmine, fills out the pages in grand anti-Protestant rhetoric; enough to earn him recognition as the dominant defender of papal power in his age.

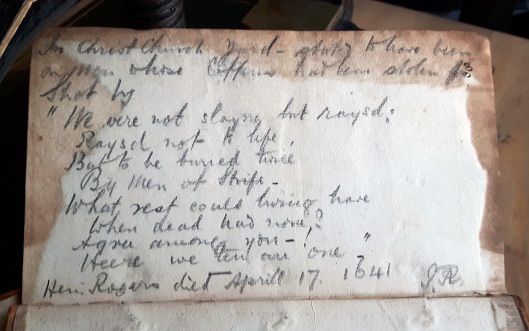

This work first appeared in print in 1581 with the production of its first volume, and Bellarmine expanded on it over the subsequent decade to build up a copious defence of the papacy. There were some lenient extracts, which may have seen the book briefly prohibited by the pope in 1590, but other parts were more on the extreme side; this certainly surprised one of the books owners.

So, why are my volumes interesting enough to be off the shelf and in this blog post?

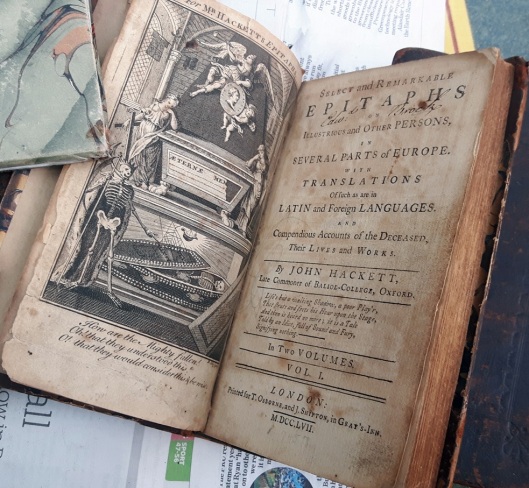

I bought the first volume several years ago now; it was the first 16th century book that I owned, a proud Parisian volume bound in contemporary – possibly English – calf boards with an 18th century spine.

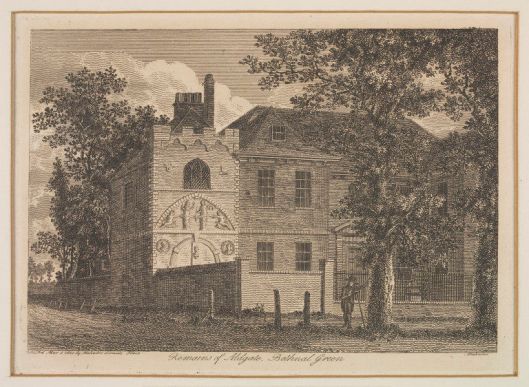

It had been owned originally by George Carleton, a famous bishop and theologian in Elizabeth I’s time, and is signed Sr. T. G. and Thomas Gage; probably the same person – a little known Baronet from Sussex. Extraordinarily, though, he was a descendant of Thomas Darcy, who owned the manor of my village almost 500 years ago.

About four years later I saw a second volume appear on eBay; I took a casual look at it because it was printed only a few years after my first volume. Amazingly, although it was in a completely different early 19th century binding, the signatures on the title page matched my first volume. This was the second volume of this set, which had apparently been split up some time between the last matching ownership inscription (1971) and me purchasing the first book. Obviously, I had to buy it; and by doing so I reunited these two fabulous books.

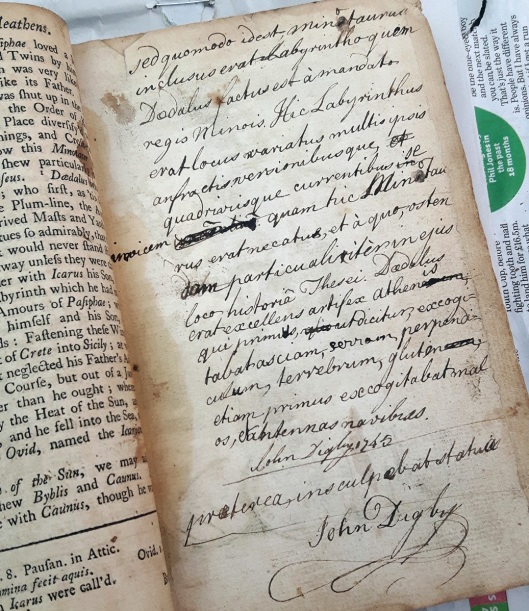

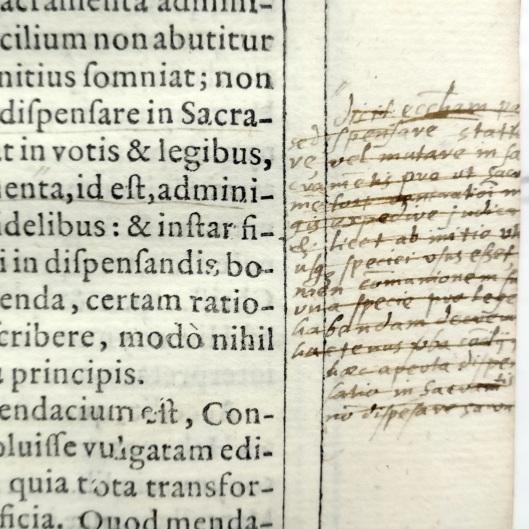

The best part of these books is yet to come, though. George Carleton, the probable first owner of the books, wrote a book as a response to the Disputationes at the start of the 17th century. These two volumes I own were clearly his reference material for this work, and nearly every page has some marginal notes from him regarding his thoughts and responses to them. His learning is already made clear simply by the fact he uses a mixture of English, Latin, and Ancient Greek to annotate the book.

Some notes he revisited and updated, as was obvious from different inks.

Whereas others he must have come back to and realised he’d misunderstood the text, or made a comment that he no longer liked.

The two books continue filled with these wonderful notes, except for one long gap in the second volume: Carleton or one of his friends must have bought him a note book for these pages, since there are simply numbers next to underlined sections – probably referring to longer notes written elsewhere.

The rebacking of the first volume at the end of the 18th/beginning of the 19th century meant the pages were recut, destroying the edges of the notations, and the same occurred to the second volume when that was entirely rebound. Although this must have happened within a decade or so, the bindings are entirely different – which is perplexing since they must have been in the same collection. One has the spine in English, while the second volume has its spine emblazoned with a different version of the title and in Latin.

The latter two owners we know about are Ralph S. Eves – most probably Rev. Ralph Shakespeare Eves, an Anglo-Catholic priest who must have taken considerable interest in this early outline of Rome’s stance against a reformed Protestant church.

The book past from him to G. B. Barrow in 1971, but this kind owner remains obscure, and I have been unable to trace him. By 2010 the two books had become separated and I bought the first volume, then six years later the second book appeared online and I bought that two, reuniting the set.

Adieu, dearest Reader.