Well-beloved Reader,

Having carefully evaded this post being adeptly edited by a cat crossing my keyboard, allow me to introduce my little work on the history of the gates of London. This first part introduces the subject and gives the history of our first gate – Bishopsgate.

PORTA LONDINIUM REDIVIVUM

or

THE GATEWAYS TO LONDON REBORN

From their Several Melancholy States of Oblivion

AN EPISTLE FOR THE READER

In a time in which the nature and availability of learning and the encouragement of curiosity have led to a celebration of idiosyncratic excellence among so many people upon so many subjects, with each person an expert upon their own peculiar field, I thought it right to produce a work in line with my own interest and amateur enthusiasm for the field of obscure historic knowledge. In this case, time and ability allowing, I would humbly present this minor work upon the many ancient gates of the City of London in their varied forms and antiquity.

These gates that you will see presented should furthermore add to the advancement of obscure knowledge, a pursuit – even a passion – that I cannot help but admire in others, and encourage in myself. Therefore allow me to delay no longer, and simply end with an apology for errors that the reader may encounter hereafter, and hope that the interesting and rare nature of this work will make up for any lack or inaccuracy in any minor part of the content.

T H E M A I N G A T E S

The wall that once surrounded London was broken by seven gates, namely Ludgate, Negate, Cripplegate, Bishopsgate, Aldgate, Aldersgate, and Moorgate. These ancient and noble structures have their roots in Roman London, where what had been a small and successful settlement had grown at an explosive rate and by the mid-2nd century was the largest city in Britain. It was not long after this, in around AD200, that the city invested in a wall – longest wall built in Britain other than Hadrian’s and the Antonine wall across the north of the country.

How long it took to build is unknown, but when finished it was five kilometres in length, six meters high and about two and a half meters thick, broken by towers and occasionally – thankfully not only for the convenience of the city, but also the cause of this work – its gates.

Roman London had four main gates to begin with; Bishopsgate, Aldgate, Newgate, and Ludgate; the former two of these guarding the principal roadways to Colchester and York – the two other main cities of Roman Britain. One of the other seven main gates mentioned previously also appears at this time, Cripplegate, which rather than being a main city gate was one of the small gates that led into the connected Roman fort.

Working with that chronology, I will begin with a description of those five most ancient gates.

B I S H O P S G A T E

The north gate to the city, this was the gateway that connected the entire of Northern Britain with what would evolve to become the heart of the country. In Roman times there was less than half a kilometre between the gate and the forum, the centre of government and commerce for the city, which lay almost directly south of the gate. At this time the side of the gate without the city would have been guarded by a two metre deep dry ditch, crossed either by a static or removable bridge.

During Roman times a cemetery developed beyond the gate, which the road leaving the city would have passed by, this fell into disuse by Saxon times and the history of the gate remains naturally vague throughout the famous dark ages, but was likely repaired or even rebuilt at the end of the 7th century by Earconwald, Bishop of London. It is very probably this man that the gate was named for.

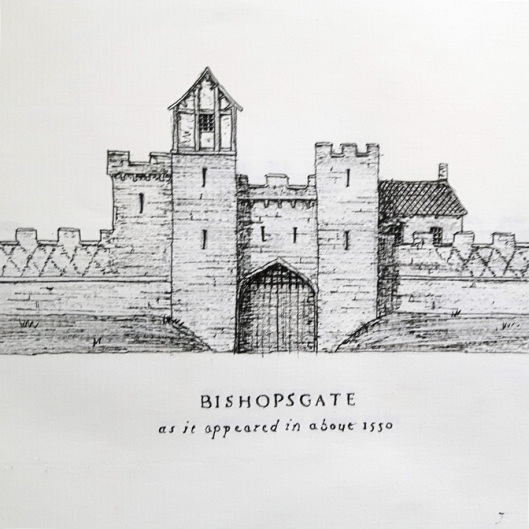

Following the Norman invasion it would seem that the defences of London were regularly improved and modified and the gates were adapted to medieval warfare too – Bishopsgate was rebuilt by the Bishop of London in William the Conqueror’s time. I think here another cause for the name could be suggested, since even though four centuries had passed it is the Bishop of London who paid for this construction too, so it is possible that in early medieval London this gate was the property of the bishop, or he held the right to repair it. This did not continue though, and Henry III granted the care of the gate to the guild of Hanse merchants, an originally German confederation of merchants that in their heyday were eminent across northern Europe. It was their turn to rebuild the gate in 1479.

There was planned to be a new rebuilding of the gate in the early 1550s, but this was cut short after the materials had been gathered and plans made, when their monopoly on much of the English merchant world tumbled, and the king seized all their property.

Unlike many of the other gates, it appears that Bishopsgate was not used as a jail, and avoided many changes that such a purpose necessitated to other gates of the city. The gate also escaped the Great Fire of 1666, with the flames being stopped before they reached it with fire breaks ‘at the upper end of Bishopsgate-street’.

By this time the medieval structure was one of the most complete of any of the other London gates, the only parts that were post-medieval additions being apparently several statue niches – one in each tower and one over the gate – the removal of the battlements and possible shortening of each of the towers either side of the gate, and the addition of two pedestrian archways, running through the base of each tower.

The lack of uses for this gate, however much they had preserved it so far, (the others being put to use as jails, commercial premises, or lodgings) meant that without a military need to maintain it the gate became neglected and was in the end pulled in 1731, having been used by Carvers, an officer working under the Lord Mayor, for several years previously. A neo-classical gate was built to replace it, which lasted less than three decades, and was demolished in 1760.